Penguin Diplomacy - the

life story of Brian Roberts

polar explorer, Antarctic treaty maker

and wildlife conservationist

Ornithology

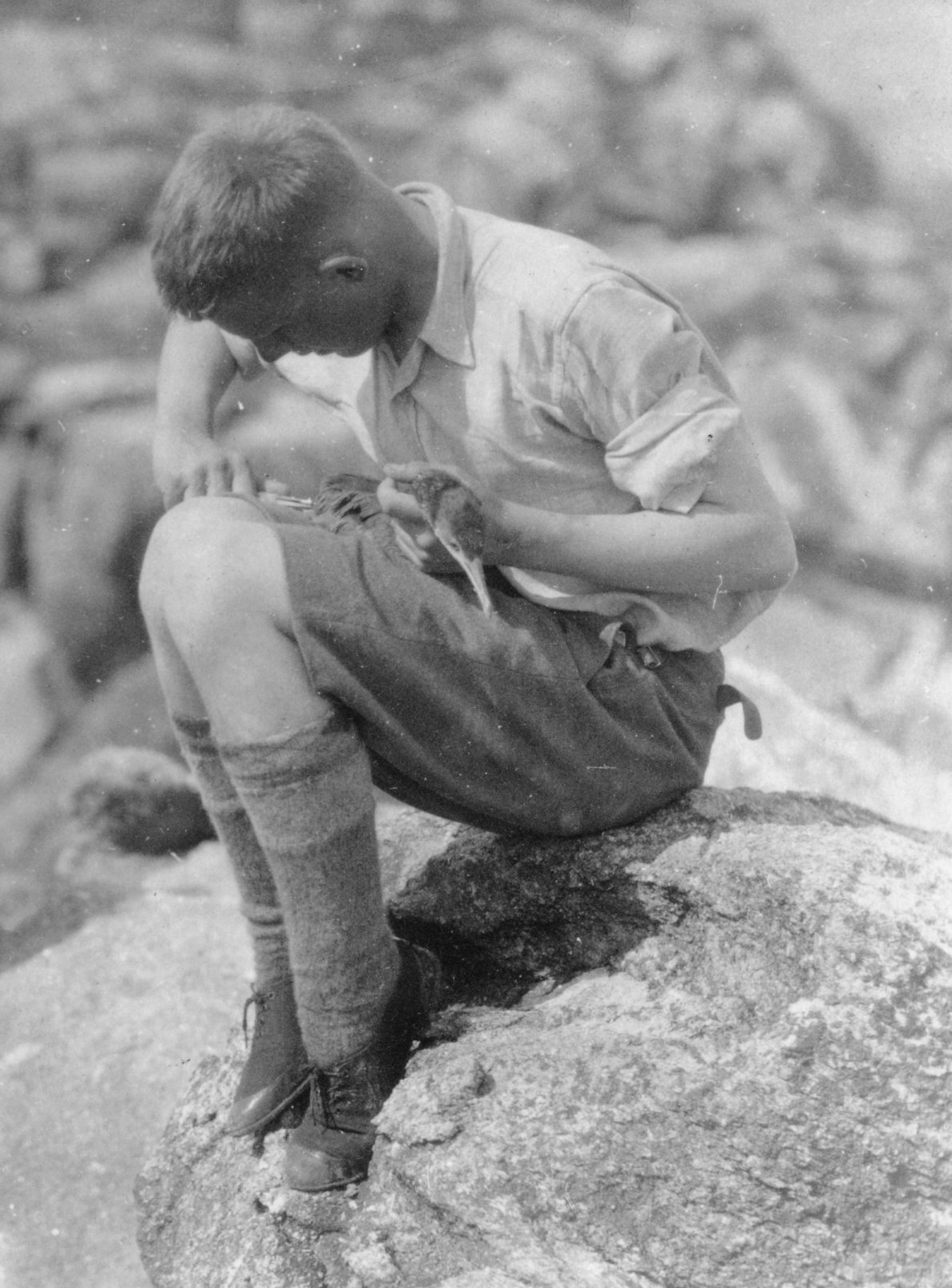

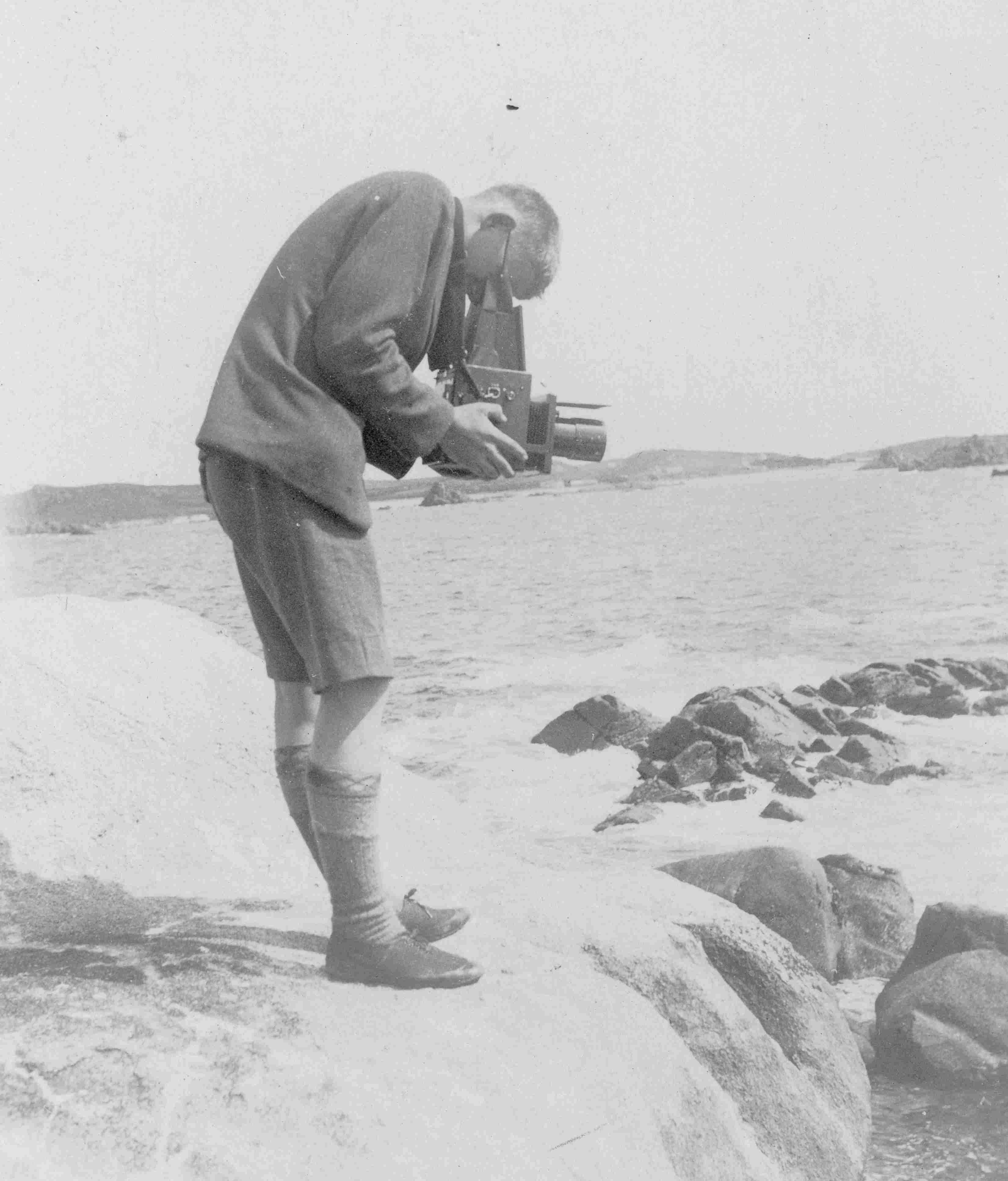

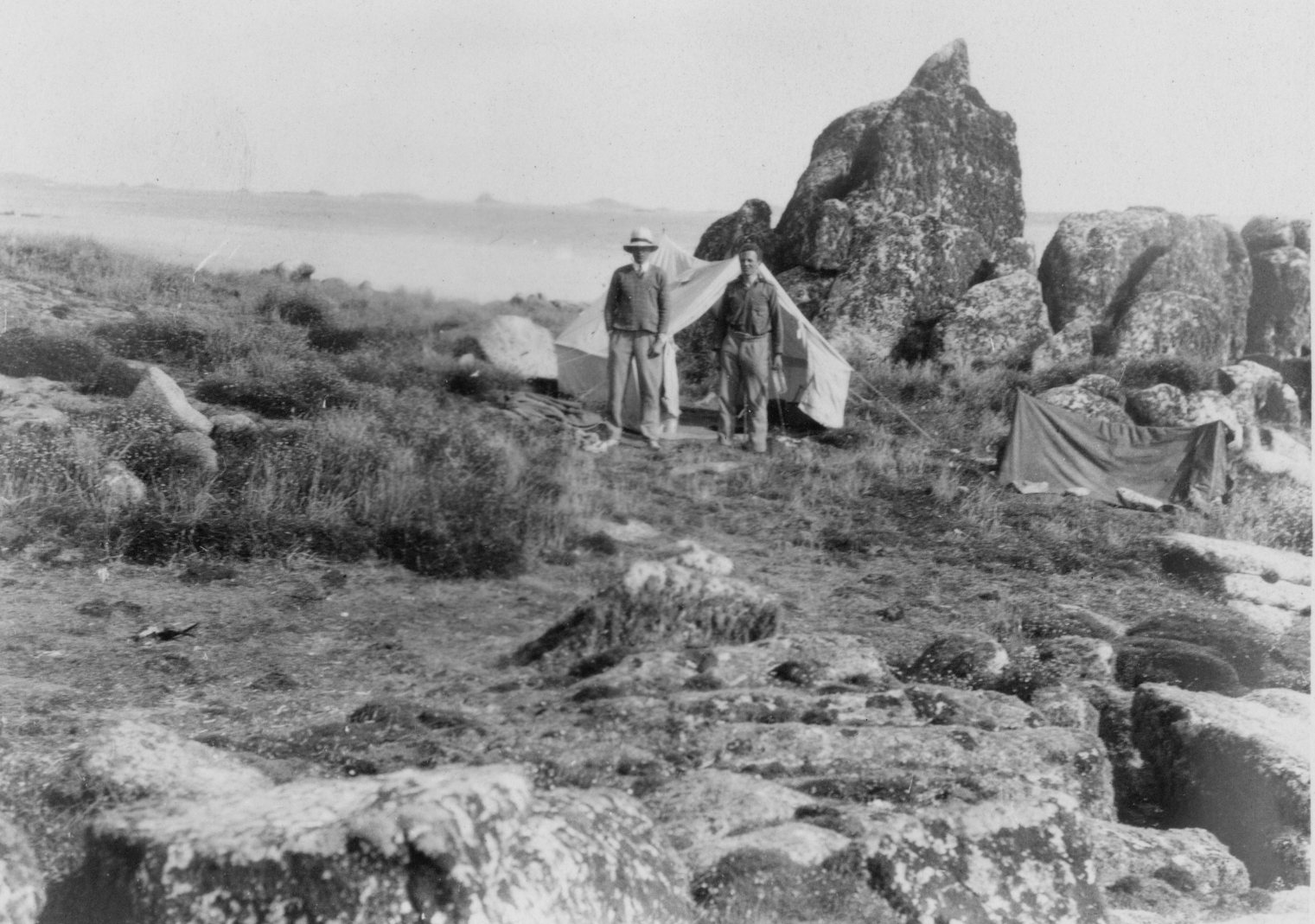

Brian Roberts’ passion for birds began at a tender age well before he started school. He was particularly drawn to seabirds. By his mid-teens he was able to exert strong leverage on his accommodating family when it came to holidays: no relaxing at some fashionable seaside resort but rather an exploration of some remote uninhabited islands in an open boat at the mercy of the weather. His father Charles was an accomplished photographer, and taught the 15-year old Brian how to operate a heavy plate glass camera.

Bird ringing

|

|

|

In the 1920s all that was known about the European storm petrel and Manx shearwater came from dead specimens. Every detail of their colour variation, feathers and size could be found in Witherby’s Handbook of British Birds. But there was no mention of where they breed nor how many eggs were laid. Why was there this omission? Being nocturnally active species at breeding time (to avoid predators) they had never been studied, and Brian spent his nights observing the activities of shearwaters. Daytime was spent hunting amongst the massive storm boulders for well-hidden storm petrel nests.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pioneering work in the Antarctic

Roberts was in his final year at Cambridge when he was invited as ornithologist to join a major overwintering expedition to the Antarctic, led by the Australian John Rymill. The British Graham Land Expedition (BGLE, 1934-37) took place at a time of economic recession and was organised on a shoestring. An old Breton sailing ship Penola was refitted to take the Expedition south. Without the expense of a dedicated crew, the expedition team had to learn to sail her under the expert eye of her captain, Robert Ryder. Penola was a beautiful sight in a fair wind, but she was beset by serious engine troubles from the outset and most of her long voyage had to be made under sail alone.

Roberts was looking forward to joining the long sledging trips planned for exploring Graham Land’s topography far south. Was it a collection of islands, as was believed at the time due to aviator Hubert Wilkins’ pioneering flights in 1928, or could it be actually a peninsula?

BGLE had many dramas along the way, but everyone returned safe and sound. The one who came closest to death’s door was Roberts himself. Laid low by several bouts of appendicitis, he only just avoided a kitchen table appendectomy and recovered from the brink of a burst appendix. The result was a transfer to the ship’s party, and Roberts was sent back north to the Falkland Islands on the Penola, to have his appendix out at Port Stanley. This created opportunities for some serious sub-Antarctic ornithology as Penola shuttled between Deception Island, the Falklands, South Georgia and the north Graham Land coast. At numerous sites around the Antarctic he opportunistically snatched time to record the breeding behaviour of the widely distributed but unstudied gentoo penguins. This would not have happened had he stayed healthy and gone with the shore party, as southern Graham Land has almost no bird life.

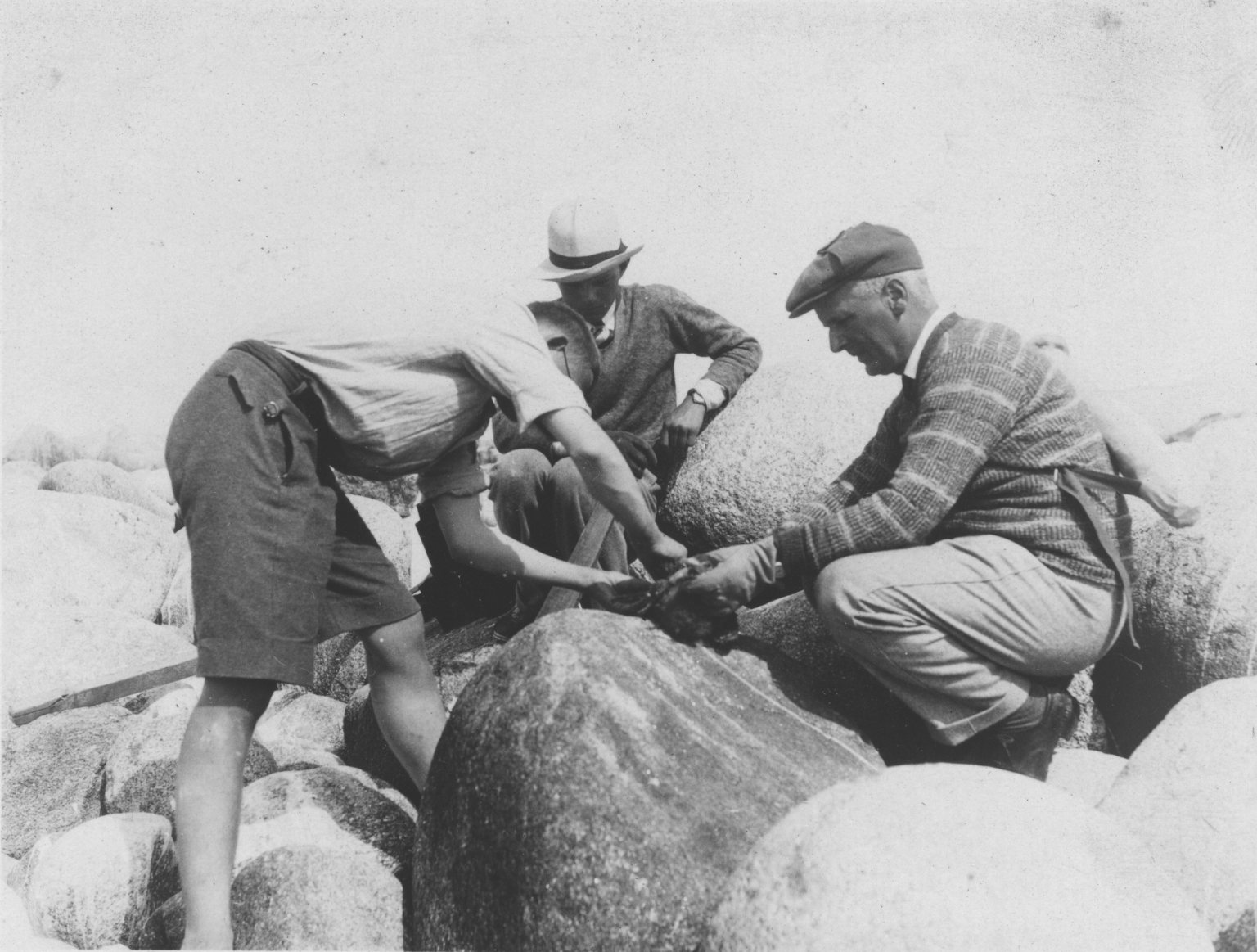

During the expedition’s first year a northern base was set up on the low-lying Argentine Islands,

where Roberts found an accessible colony of Wilson’s storm petrel in a mossy cliff bank. Using

the technology of the day he made a pioneering study of the complete breeding cycle of this

little bird. He ringed a number of them, and when Penola returned

one year later, to his joy he found that most of his birds were back in the same burrow and with the same

mate, having migrated an astonishing 9000 miles to the Arctic and back: one of the longest of any

bird.

During the expedition’s first year a northern base was set up on the low-lying Argentine Islands,

where Roberts found an accessible colony of Wilson’s storm petrel in a mossy cliff bank. Using

the technology of the day he made a pioneering study of the complete breeding cycle of this

little bird. He ringed a number of them, and when Penola returned

one year later, to his joy he found that most of his birds were back in the same burrow and with the same

mate, having migrated an astonishing 9000 miles to the Arctic and back: one of the longest of any

bird.

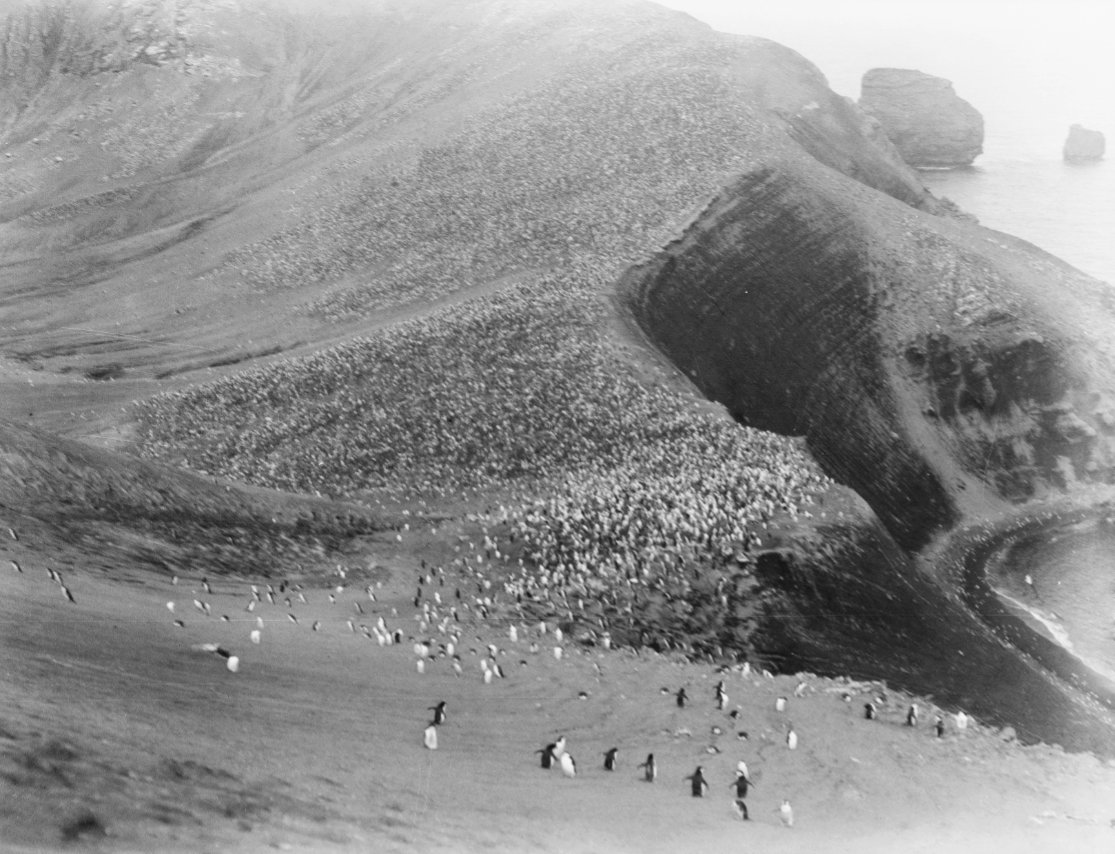

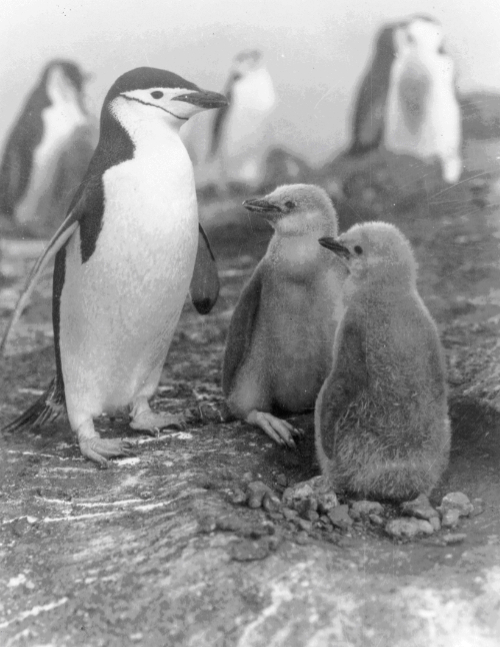

Deception Island holds one of the world’s largest chinstrap penguin colonies at Baily Head, which Roberts visited several times. Full of enthusiasm he ventured right into the middle of it, only to wish he hadn’t. Chinstraps are the feistiest of the brushtail penguins, and Roberts was pecked remorselessly on the legs by their sharp beaks. Surrounded by an ear-splitting din from angry birds protecting their chicks, he had to beat a hasty and undignified retreat. But he was the first to make a count here: a conservative estimate of 145,000 birds.

|

|

On South Georgia Roberts had to help with the physically arduous refit of the ship in the unpleasantly cold, wet and windy conditions of an austral winter. He subsequently got his reward when Penola left for the Falklands and he was left alone. He persuaded some of the sealers to take him out on their catchers. Turning his back to the slaughter on the beaches he headed inland to record nesting sooty albatross.

|

|

Here Roberts joyfully made his first acquaintance with king penguins. He collected eggs to study embryonic development, mapped the rookeries, and made a rough census of each colony. Since king penguins have a unique breeding cycle of 10-13 months to raise a chick, at any one time in a colony there will be birds at different stages of breeding and chick development. Counting a large colony such as this one in the Bay of Isles is a challenge, particularly in a blizzard!

Whilst out with the research ship Discovery 11, Roberts grabbed a rare weather opportunity to visit an almost unexplored sub-antarctic island in the South Shetland group. Like its famous neighbour Elephant Island, Clarence Island is extremely challenging to land on. With two other scientists the determined Roberts landed by small open boat next to a large chinstrap penguin colony and proceeded to climb the vertiginous cliffs carrying a heavy plate camera. His reward was to find colonies of silver grey petrels (southern fulmar) and cape petrels. Roberts was the first ornithologist to land on Clarence Island.

Back in the Falkland Islands Roberts was in his element, studying rockhopper and Magellanic

penguin colonies as well as blue-eyed shags, night herons and sooty shearwaters. On Kidney Island he camped

alone, studying the sooty petrels in their burrows in the dead of night. A task not for the faint-hearted:

h e would emerge covered in fleas from the birds, and needed to de-flea himself every few hours.

Reaching their burrows meant a climb up narrow twisty paths around the clumps of tussock in the dark trying to

avoid sleeping sealions, which would have given him a nasty bite if disturbed.

e would emerge covered in fleas from the birds, and needed to de-flea himself every few hours.

Reaching their burrows meant a climb up narrow twisty paths around the clumps of tussock in the dark trying to

avoid sleeping sealions, which would have given him a nasty bite if disturbed.

All the penguins Roberts studied during BGLE are sub-Antarctic species: gentoo, chinstrap, rockhopper and king penguin. Some years later the highlight of an otherwise rather dispiriting US expedition Operation Deep Freeze 1961 was a visit to see the one truly Antarctic species. Cape Crozier is the site of the emperor penguin colony made famous by Apsley Cherry-Garrard in The Worst Journey in the World. Numerous sketches, detailed maps and watercolour paintings had been made by artist and doctor Edward Wilson. With no easy access to the colony, Roberts was dropped by helicopter to camp half a mile away. He was rewarded by the sight of well-grown chicks being fed by their parents, some already moulting their down in early summer.

Warmer climes

Since childhood Roberts had dreamed of visiting the widely scattered and remote French sub-Antarctic islands in the Indian Ocean administered by TAAF (Terres Australes et Antarctiques Françaises). The chance came at last in 1964 when he was invited to join TAAF’s provisioning ship MS Gallieni. The richness and diversity of birdlife on these islands was already known, albeit not well recorded. The voyage took him from the tropical island of Réunion where he found the exquisite white-tailed tropicbird, to the world’s largest population of king penguins on Iles Crozet, which also had 4 nesting species of albatross. Wandering albatross, fearless of his presence, were feeding their young on the nest and he was able to watch from close quarters. On the main island of Kerguelen he revelled at being able to sit amongst a colony of fearless black-browed albatross as they incubated their single egg on a raised cup-shaped nest of mud. During the long periods of sailing between the islands there was abundant bird life to observe. Back at Réunion Roberts had a rare opportunity to fly to the tiny coral island of Tromelin, unoccupied except for a meteorological station. The mile-long sandbank was home to breeding green turtles, a large number of nesting red-footed boobies, a few of the larger white boobies, and Lesser and Magnificent frigatebirds. Roberts wished that he had brought twice as much film with him. Sadly, his prolific photographic record from this journey seems to have been lost.

|

|

|

|

All images on this website are the copyright

of the authors of Penguin Diplomacy

ed ringers to submit their records to his magazine British Birds. Brian persuaded

his long-suffering family

ed ringers to submit their records to his magazine British Birds. Brian persuaded

his long-suffering family